My Kibera Sister

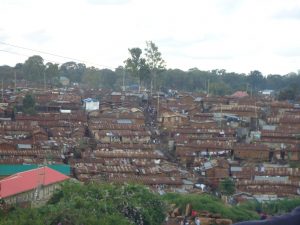

My Kibera sister rises just before the sun begins to poke out from beneath the horizon. She can hear the scratching of rats scampering around above her. Her four children are still asleep in the crowded room, with its four red mud walls and tattered tin sheet roof trying its best to protect them from the challenges of the slum around them. Two of the children are huddled close together on the dirt floor in an attempt to stay warm despite the dampness that permeates the room. The other two, in their good fortune, are under layers of blankets in the twin bed, at the feet of where their momma slept. Dangling from a clothesline across the room, is a threadbare sheet, which acts as a  wall to give the illusion of privacy within the tiny space. She pushes it back, and picks up her basin and the heavy yellow jerry can from the corner of the room and begins to pour splashing water into the pan. She puts on her flip flops and grabs the string with the two keys hanging from nail on the wall. Then she unfastens the padlock and balances the basin of water as she steps outside her door. Brown, heavily packed dirt surrounds her, and above the dirt lies tiny house after house, each one created with the same dirt, each one squashed together, almost on top of the next. She is one small person engulfed in this chocolate city. There is a stream of sewage to the right and empty milk packages, banana peels, plastic bags, tin cans, and corncobs surrounding her to the right. But she walks forward around the corner, ducking underneath the neighbor's freshly hand-washed laundry hanging to dry, through a small alley, also littered with trash, past the large water tank where her family comes to collect water each day, to the shared neighborhood "toilet." The toilet is merely an outhouse with a hole in the ground surrounded by a cement slab, and a creaking wood door. Next to it are the "showers," which are simply a room, no bigger than the size of the outhouse, with the same creaking door, and a cement floor without a drain. There is no water in the shower, and that is why she has carried the basin.

wall to give the illusion of privacy within the tiny space. She pushes it back, and picks up her basin and the heavy yellow jerry can from the corner of the room and begins to pour splashing water into the pan. She puts on her flip flops and grabs the string with the two keys hanging from nail on the wall. Then she unfastens the padlock and balances the basin of water as she steps outside her door. Brown, heavily packed dirt surrounds her, and above the dirt lies tiny house after house, each one created with the same dirt, each one squashed together, almost on top of the next. She is one small person engulfed in this chocolate city. There is a stream of sewage to the right and empty milk packages, banana peels, plastic bags, tin cans, and corncobs surrounding her to the right. But she walks forward around the corner, ducking underneath the neighbor's freshly hand-washed laundry hanging to dry, through a small alley, also littered with trash, past the large water tank where her family comes to collect water each day, to the shared neighborhood "toilet." The toilet is merely an outhouse with a hole in the ground surrounded by a cement slab, and a creaking wood door. Next to it are the "showers," which are simply a room, no bigger than the size of the outhouse, with the same creaking door, and a cement floor without a drain. There is no water in the shower, and that is why she has carried the basin.

After freshening up, my Kibera sister returns to her home. The kids are now awake, and it is only 5:00 a.m. She brings her charcoal stove outside the house and begins to build a small fire for cooking the chapati she will sell to the neighbors. She fans the flames and waits as each small piece of charcoal from the forest slowly begins to light. As she waits, she mixes flour with water from the jerry can and kneads them together with her hands. She uses the small coffee table in her house, one of only 3 pieces of furniture she owns, to roll out each chapati, coat it with oil, and roll it back into a cinnamon bun shape before rolling it out one final time and then individually frying each piece. It is a slow, time-consuming process, but one that will earn her a dollar or two if she is lucky; one that will allow her to feed her children dinner tonight. Last night she had to decide how she would spend her 200 shillings ($2) she had earned from making chapati. Should she pay her daughter's school fees so that the girl wouldn't be sent back by the headmaster? Or should she buy maize to feed the hungry bellies of her children? Nearly every day my Kibera sister is faced with these tough choices. There is never a right answer.

As the chapati finishes, she boils black tea, and skips adding the milk that her family loves so much--the 50 shillings that it costs is more than she can afford today. The kids scrape the last morsels of sugar from the bowl into their tea as they laugh and make jokes. My Kibera sister is tired and weary from her struggles, but she does not complain. Instead she gathers her family together to pray and thank God for the gift of life which has allowed them to see this new day.

My Kibera sister sends her sends her children off to school by 6:00 a.m. She urges them to stick together and not to stop and talk. They walk nearly 30 minutes across the slum to their primary school. Though a button is missing from her son's shirt, and her daughter's sweater has a hole in the sleeve, their uniforms are pressed and clean. Their black shoes are polished, so as to avoid punishment at school. The children chat happily as they walk down the dirt path carrying their backpacks, all with broken zippers, that barely stay closed. Independent but young, the oldest daughter leads them all together.

My Kibera sister still has much of the day in front of her. She will walk to her next job, nearly 30 minutes away. She will work tirelessly until evening. Her children will stay at school until nearly 5:30 pm. Then she will return home to carry water back to her house, to hand wash her clothes, and try to find kerosene so that her children can see to do their homework in the dark. She will sing with them and tell stories to them. She will usher them inside before night fall because no one dares to walk around Kibera once the sun goes down. There are rapings and beatings and neighbors staggering home after enjoying their illicit, and sometime blinding, brews. There are so many dark things that she will try to shelter from her children's eyes and ears. But she will remind them of the good things--the African music from local shops that pours out into the streets, the sweet smell of mandazi bubbling in the oil, the sense of community and togetherness of each neighbor nearby, the football matches broadcast on the shop tv down the road, vibrancy of dances and performances throughout their community each week. And most importantly, she will teach them to be strong, to rely on the One who is greater than the darkness. She will teach them to have hope because tomorrow is always another opportunity for something better.